Table of Contents

- Introduction to Factor Inhibitor

- What Is a Factor Inhibitor?

- Types of Factor Inhibitors

- ‘Factor Inhibitor’ in Hemophilia and Bleeding Disorders

- Causes and Risk Factors of Factor Inhibitor Development

- Pathophysiology of Factor Inhibitor Formation

- Clinical Signs and Symptoms

- Laboratory Diagnosis of Factor Inhibitor

- Bethesda Assay and Its Importance

- Management and Treatment Strategies

- Role of the Laboratory in Factor Inhibitor Monitoring

- Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

- Prevention and Patient Education

- Importance of Factor Inhibitor Awareness in Clinical Practice

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Conclusion

Introduction to Factor Inhibitor

Factor inhibitor is a critical and often complex topic in hematology that directly affects the diagnosis, treatment, and long-term outcomes of patients with bleeding disorders. A factor inhibitor refers to an antibody that interferes with the normal function of clotting factors, making standard replacement therapy less effective or completely ineffective. Because of its clinical significance, understanding factor inhibitor development is essential for clinicians, laboratory professionals, and healthcare students.

Factor inhibitor formation represents one of the most serious complications in patients receiving coagulation factor replacement therapy. Its early detection and proper management can significantly improve patient outcomes.

What Is a Factor Inhibitor?

A factor inhibitor is an alloantibody or autoantibody that neutralizes the activity of specific coagulation factors, most commonly factor VIII or factor IX. These antibodies bind to infused or endogenous clotting factors and block their ability to participate in the coagulation cascade.

When a factor inhibitor is present, patients may experience persistent bleeding despite receiving appropriate factor replacement therapy. This makes factor inhibitor identification a vital step in the evaluation of unexplained bleeding episodes.

Types of Factor Inhibitors

Factor inhibitor conditions can be broadly classified based on their origin and target factor:

1. Alloantibody Factor Inhibitor

These inhibitors develop in patients with congenital bleeding disorders, particularly hemophilia A and hemophilia B, after exposure to replacement therapy.

2. Autoantibody Factor Inhibitor

Autoantibody-related factor inhibitor occurs in individuals without inherited bleeding disorders. This condition is often referred to as acquired hemophilia.

3. Specific Factor Inhibitors

- Factor VIII inhibitor (most common)

- Factor IX inhibitor

- Factor V inhibitor

- Factor XI inhibitor

3. Specific Factor Inhibitors

- Factor VIII inhibitor (most common)

- Factor IX inhibitor

- Factor V inhibitor

- Factor XI inhibitor

Each factor inhibitor type presents unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Factor Inhibitor in Hemophilia and Bleeding Disorders

Factor inhibitor development is most frequently associated with hemophilia A. Approximately 20–30% of patients with severe hemophilia A develop a factor inhibitor at some point in their lifetime. In hemophilia B, factor inhibitor development is less common but often more severe.

The presence of a factor inhibitor transforms a manageable bleeding disorder into a high-risk clinical condition, requiring specialized care and alternative treatment strategies.

Causes and Risk Factors of Factor Inhibitor Development

Several factors contribute to the development of a factor inhibitor:

- Genetic mutations affecting clotting factor structure

- Family history of factor inhibitor

- Intensity and frequency of factor replacement therapy

- Early exposure to clotting factor concentrates

- Immune system activation due to infection or surgery

Understanding these risk factors helps clinicians anticipate and monitor factor inhibitor formation.

Pathophysiology of Factor Inhibitor Formation

Factor inhibitor formation is an immune-mediated process. The body recognizes infused clotting factors as foreign antigens and produces antibodies against them. These antibodies bind to functional sites on the factor molecule, preventing its role in clot formation.

The immune response involved in factor inhibitor development is complex and includes antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and B-cell antibody production.

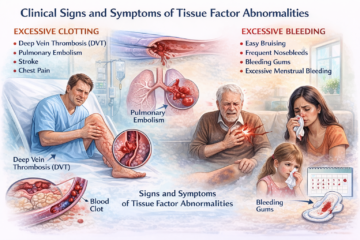

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Patients with a factor inhibitor may present with:

- Unexpected bleeding episodes

- Poor response to factor replacement therapy

- Prolonged bleeding after trauma or surgery

- Soft tissue or muscle hematomas

- Life-threatening hemorrhage in severe cases

Recognizing these symptoms early is essential for prompt diagnosis of factor inhibitor.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Factor Inhibitor

Laboratory testing plays a central role in identifying a factor inhibitor. Common diagnostic findings include:

- Prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)

- Failure of aPTT correction in mixing studies

- Reduced factor activity levels

Confirmatory testing is required to quantify the factor inhibitor titer.

Bethesda Assay and Its Importance

The Bethesda assay is the gold standard test for measuring factor inhibitor levels. It quantifies the inhibitory strength of antibodies against clotting factors and reports results in Bethesda Units (BU).

A higher Bethesda Unit value indicates a stronger factor inhibitor, which directly influences treatment decisions and prognosis.

Management and Treatment Strategies

Management of factor inhibitor depends on inhibitor type and titer:

- Bypassing agents (activated prothrombin complex concentrate, recombinant factor VIIa)

- Immune tolerance induction therapy

- Immunosuppressive treatment for acquired factor inhibitor

- Supportive care during bleeding episodes

Individualized treatment plans are essential for effective factor inhibitor management.

Role of the Laboratory in Factor Inhibitor Monitoring

Laboratories play a vital role in:

- Early detection of factor inhibitor

- Monitoring inhibitor titers over time

- Assessing treatment effectiveness

- Supporting clinical decision-making

Accurate laboratory reporting ensures optimal patient care in factor inhibitor cases.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

The prognosis of patients with a factor inhibitor varies widely. Low-titer inhibitors may resolve spontaneously, while high-titer inhibitors often require long-term treatment. Early diagnosis and appropriate therapy significantly improve outcomes.

Prevention and Patient Education

Preventive strategies include:

- Regular inhibitor screening

- Careful monitoring during early factor exposure

- Patient education on bleeding symptoms

- Multidisciplinary care approaches

Educating patients about factor inhibitor risks empowers them to seek timely medical attention.

Importance of Factor Inhibitor Awareness in Clinical Practice

Awareness of factor inhibitor is crucial for healthcare professionals involved in hematology, transfusion medicine, and laboratory diagnostics. Prompt recognition and intervention can prevent serious complications and reduce healthcare burden.

Conclusion

Factor inhibitor is a complex but essential topic in modern hematology. Its impact on patient outcomes, treatment strategies, and laboratory diagnostics cannot be overstated. A strong understanding of factor inhibitor mechanisms, diagnosis, and management is vital for ensuring safe and effective care for patients with bleeding disorders.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is factor inhibitor life-threatening?

Yes, untreated factor inhibitor can lead to severe or fatal bleeding.

Can factor inhibitor be cured?

Some factor inhibitor cases resolve with immune tolerance or immunosuppressive therapy.

Is factor inhibitor dangerous?

Yes, untreated factor inhibitor can result in severe or fatal bleeding complications.